Harold Cohen was a British artist who lived in California since 1968 until his death in 2016. His major interest in art has always been the dimension of color. However, for several decades he also concentrated on the representation problem, as he occasionally called it: How few lines or marks does it take to generate an image that people recognize as representing something specific in their experienced world? In the early 1960s, Cohen had already been successful as a painter—convincingly demonstrated by his participation at documenta III _(Kassel, Germany) in 1964, and at the 33rd _Venice Biennale in 1966 (as one of five representatives for the UK). After moving to California in 1968, he soon came into close contact with computers and their capabilities.

He moved to San Diego to take on a series of positions at the University of California there: he was a visiting lecturer in 1968/69, a visiting professor and acting chairman of the Visual Arts Department from 1969 to 1970, after this a professor and chairman there (until 1971), and a professor after this.

Upon a recommendation by Paul Brach, after Cohen chairman of the Visual Arts Department, he met Jeff Raskin, a young student in the music department with an interest in computing. Brach thought, computers and programming could be a good way for Cohen to further develop his art. “Computers? Sure, why not?” is how Cohen recalls that anecdote. Raskin showed Cohen what the technique of flowcharts could be good for in developing algorithms for drawing or painting. This episode ended when Raskin, upon Cohen’s request, gave him a Ditran (Diagnostic Fortran) manual. Cohen now was on hisown to learn programming.

Cohen began investigating methods of Artificial Intelligence for applications in fine art. In 1970 he met Edward Feigenbaum, who invited him to the AI Lab at Stanford University. He there was a visiting scholar from 1973 to 1975. Cohen informally learned the programming language SAIL, which at the AI Lab was the most used for memory-intensive and real-time applications. Cohen needed this level of performance for the real-time exhibitions he was preparing.

During the 1970s, he constructed computer-controlled drawing machines. His first one was on display at the 1971 Fall Joint Computer Conference at Las Vegas.

His first code controlled a drawing gadget called “Turtle”, similar in function as the MIT Turtle_: it was moving on the floor, equipped with a pen, leaving graphic marks behind. Cohen’s device moved by spinning two wheels at different speeds, which resulted in smooth curves. The _Turtle_"knew" via a sonar navigation system, where on the drawing it was at a given moment—a feature necessary to control the device on an area of three by nine meters.

Cohen’s program, soon and forever called AARON, made its first public appearances at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1972, and the La Jolla Museum in 1973. The Turtle went on display at documenta VI at Kassel, Germany in 1977. (documenta is one of the most prestigious exhibitions of fine art worldwide.) It was also in the center of attraction for shows at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, and the Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco.

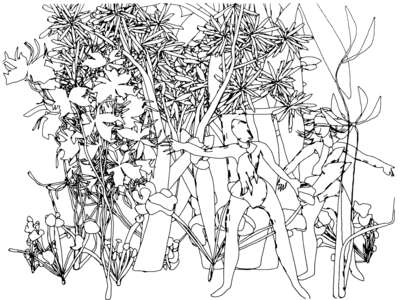

Cohen developed AARON into an enormously powerful and complex rule-based system. In the 1990s, he replaced the drawing machines by painting machines (now in the permanent collection of the Museum of Computing History in Mountainview, CA). Typical subject matters were portraits of “imagined” people, as well as still-lifes.

In 2002, he abandoned the painting machines in favor of wide-format printers. Although color had been central to his work all along, it was not until 1985/86 that he began to see how a program without vision could become an expert colorist. The resultant rule-based system became intractable by the end of 2005, when he replaced it by an algorithm, which AARON has been using ever since.

When in the last few years of his life he was no longer capable of standing in front of a canvas and paint, he transformed himself into a digital finger painter. He installed a system consisting of a huge touch screen and a personal computer with a large but common. sized screen. The line-generating algorithm from AARON produced black free-hand curves displayed on the big touch-screen; the artist selected a color on the ordinary screen; when he now moved his finger on the touch-screen, it left traces of the selected color.