Cybernetic Serendipity was the first large international exhibition of electronic, cybernetic, and computer art. It took place at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London, UK, from 2 August to 20 October 1968.

There are reports saying that between 44,000 and 60,000 people visited the show during its more than two months duration. However, ICA did not take real counts.

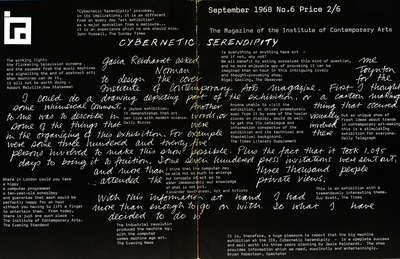

Jasia Reichardt was the show’s chief curator. She headed a team also comprising Franciszka Themerson (exhibition and graphic design from Gaberbocchus Press, London); Mark Dowson (technological advisor from System Research Ltd., London); Peter Schmidt (music advisor, London).

The idea for the show had emerged when Max Bense visited the 1965 exhibition of concrete poetry at the ICA and responded to Reichardt’s question, “what should I do next?”, by suggesting, she should look into computers. (It should be noted that only shortly before, on 5 February 1965, Bense had opened the first ever show of computer generated art in his Studiengalerie at Technische Hochschule (later: University) Stuttgart.

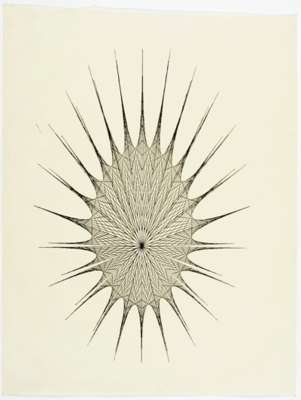

Cybernetic Serendipity was the first exhibition to attempt to demonstrate all aspects of computer-aided creative activity: art, music, poetry, dance, sculpture, animation. The principal idea was to examine the role of cybernetics in contemporary arts. The exhibition included robots, poetry, music and painting machines, as well as all sorts of works where chance was an important ingredient.

Cybernetic Serendipity was organised in three sections:

• computer generated work

• cybernetic devices-robots and painting machines

• machines demonstrating the use of computers and the history of cybernetics.

The exhibition dealt with an exploratory field, it aimed at INSIGHTS and FORESIGHT. One statement claimed, “one can foresee the day when computers will replace railway trains and airliners as the cult symbols of the under twelve’s”. Possibilities rather than achievements were its domain, and in this sense it was prematurely optimistic.

Parts of the show were shipped to the USA in 1969 to be displayed at the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C. Some of the exhibits were damaged during transport. After repair, they were on display in Washington and the Exploratorium in San Francisco.

What remained after the exhibited works had been sold or returned to their owners, was transfered to the Kawasaki City Museum, Japan, at the time of Jasia Reichardt’s leave from the ICA in 1971. However nothing of the material is on display there. (The Exploratorium bought some of the works in April 1971.)

Estimates are that, in one way or another, 350 people contributed to the exhibition, among them 43 artists, composers and poets, and 87 engineers, computer scientists and philosophers.

The literature about the exhibition is substantial (see pointers below). In hindsight, one could characterize it as an intellectual exercise that became a spectacular event: noisy, funny, exciting. If digital media depend on two ingredients, event and research, then the first was Cybernetic Serendipity in London, and the second Tendencies 4 in Zagreb (at the same time, in continuation of New Tendencies 1, 1961; New Tendencies 2, 1963; and New Tendencies 3, 1965).

The year, 1968, is also the year of student protest and riots in the France, West-Germany, the USA, and other countries – not, however, in the UK. “It could not have happened elsewhere,” one critique said.

ICA staff: Hercules Bellville, Juliet Brightmore, John Brown, Michael Bygrave, Pat Coomber, Brian Croft, Sue Davis, Michael Kustow, Julie Lawson, Mimi Lipton, Mary Llewelyn, Andrew Logan, Dorothy Morland, Sir Roland Penrose, John Sharkey, Leslie Stack, Ann Sullivan, and Darcy Vaughan-Games. For further research, it might be useful to know the names of five Bath Academy of Art students, who supported Franciszka Themerson: Colin Oven, Carolyn Robinson, Diana Seymour, David Skilbeck, and Noelle Stewart.

Exhibition Catalogue : Cybernetic Serendipity. The Computer and the Arts