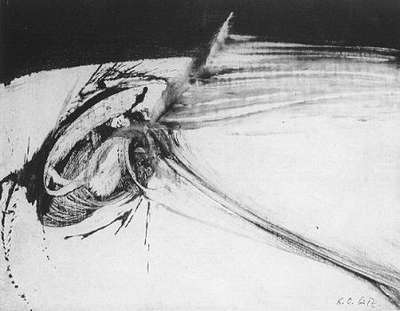

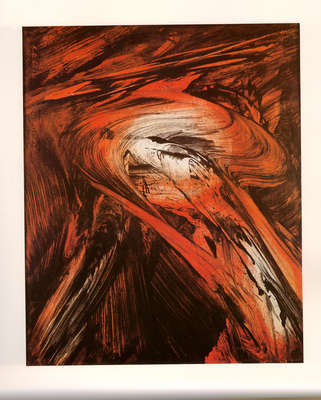

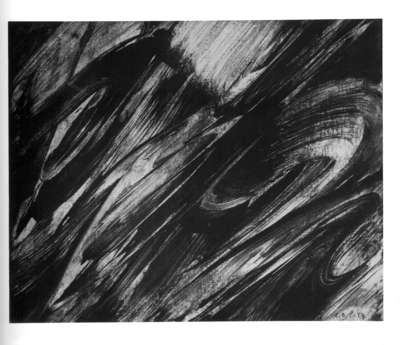

K.O. Götz – as his name is usually given – is one of the most important and most productive artists of the German Informel style (“Informelle Kunst”, a relative of Abstract Expressionism and Art Informel). His enormous production since the mid 1950s in this style is easy to distinguish from other styles and from the work of other individuals.

In postwar-Germany he is one of the most important artists. During his time as a professor at Kunstakademie Düsseldorf (from 1959 t0 1979), a large number of later famous artists were his students, among them Gotthard Graubner, Gerhard Richter, Sigmar Polke, H.A. Schult, Rissa (his later wife), and Franz Erhard Walther.

In just one sentence, Götz’ art belongs to that powerful movement that dissolved, and totally gave up, the principle of form in traditional art.

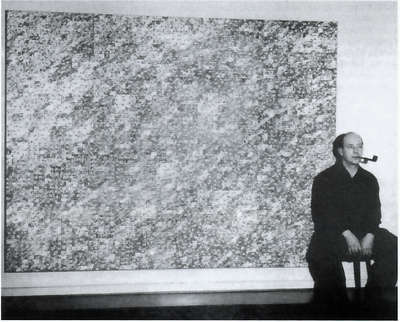

In the context of digital art it is interesting to observe that in his “Rasterbilder” (grid images) Götz for some years engaged in a totally different style. He subdivided huge canvasses into regions where each region was divided up into small grid cells. For each region, he assigned a probability measure according to which his helpers (students) determined how to color the next grid cell. (There are b/w as well as colored grid images.)

Götz unites an unceasing urge to paint directly out of his body’s movement with an intellectually rigorous analysis of the image. He was interested in the latter for reasons of an information-theoretic view of perception. Götz in his art is unconditioned body and rigorous mind at the same time. The grid images make Götz a forerunner of generative art.

A large number of later famous artists came out of Götz’ class at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf (1959-1979): among them Kuno Gonschior, Gotthard Graubner, Sigmar Polke, Gerhard Richter, Manfred Kuttner, Rissa (later his wife), HA Schult. “Man kann aus allem Kunst machen” (you can turn everything into art), was one of his beliefs. Nam June Paik, then working in Düsseldorf, said that Götz inspired him to use television for artistic experiments (that became video art).

Soon after algorithmic art came up in 1965, K.O. Götz started a discourse with Frieder Nake on matters of information aesthetics and perception. In the early 1970s, he suggested to the collector Hans-Joachim Etzold to expand his collection of constructivist art by acquiring very early computer art. Etzold gave his collection (Sammlung Etzold) on permanent loan to Museum Abteiberg in Mönchengladbach, Germany. The museum thus became probably the first in the world (1974) to have a substantial collection of early computer art (about 50 pieces).

Since about 2004, K.O. Götz has been almost blind. His thinking is active and clear as ever. In honor of his hundredth birthday, Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin put up a great exhibition of his entire work (13 Dec, 2013, to 2 March, 2014). The exhibition later went to Museum Küppersmühle für Moderne Kunst, Duisburg, and Museum Wiesbaden. A fabulous catalog was published on the occasion (K.O. Götz, Wienand Verlag Cologne).